In defense of Narnia

Every now and then I come across Christians who are either indifferent or opposed l to C.S. Lewis’ Chronicles of Narnia books series. The first group, I think, does not fully appreciate the quality and meaning of the books. The second typically dismisses them out of hand simply because the books deal with magic. It is to these groups I now wish to speak.

To the indifferent: Good stories matter

Stories matter to us as people. Stories, however, are especially important for children. Lewis understood this and, to his credit, sought to weave Christian ideals into one of the most beloved and memorable set of children’s novels in history.

Lewis said, “I thought I saw how stories of this kind could steal past a certain inhibition which had paralyzed much of my own religion in childhood. Why did one find it so hard to feel as one was told one ought to feel about God or about the sufferings of Christ? I thought the chief reason was that one was told one ought to. An obligation to feel can freeze feelings. And reverence itself did harm. The whole subject was associated with lowered voices; almost as if it were something medical. But supposing that by casting all these things into an imaginary world, stripping them of their stained-glass and Sunday School associations, one could make them for the first time appear in their real potency?”

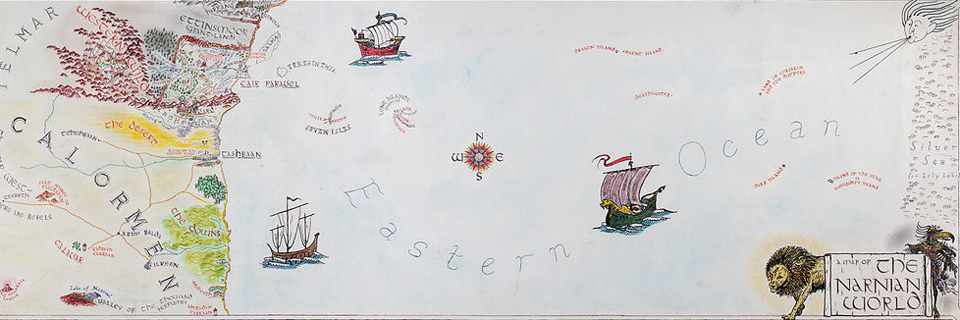

As Professor Robert C. Newmon has said, “By transferring the Gospel story to another world, where humans are not the only rational beings, where animals can talk and the various figures of classical and northern mythology have real existence, Lewis allows us to see things from a different angle. Here God is the unseen emperor over the sea, and the lion Aslan is his son and the Christ-figure of Narnia. This transfer to another world also allows Lewis to use some of the figures and symbols of the Bible as hints for his readers, just as Jesus does in His parables. So Jesus, the Lion of the tribe of Judah, becomes the Lion of Narnia.”

The Narnia characters are memorable and fully developed. They face real dilemmas and help us understand the nature of good and evil. The Narnia stories do not in any way replace the biblical narrative. It simply predisposes children toward the biblical stories. Except for certain families who only delay the inevitable, children and young people eventually will be exposed to fiction stories. Kids are going to want to read and hear stories outside the Bible, so what kind will they pick?

The fairy tale is a popular genre and children, in general, are going to pursue one of the available options. Will they choose anti-Christian literature, like the Golden Compass? Or how about Harry Potter? These two newer series are wildly popular and are not amoral. The writers are not seeking to smuggle in Christian theology into the stories, like Lewis. Christian parents would do well to steer their children toward a class in the Narnia series. In choosing fiction, parents should pick ones that favor the biblical worldview, as does Lewis.

To the opposition: A distinction with a difference

The Bible very clearly prohibits the use of magic, especially divination (see Deut. 18 and Exodus 22). Why, then, would Christians be okay with the Narnia series, which has magic in it?

The key distinction is real magic versus make-believe magic. Lewis, in creating Narnia, has invented another realm that operates in a different temporal scheme. In other words, when Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy are transported from England to Narnia, the realities in which they operate change. The children (and adults) reading them are also whisked away to another time and place.

Yet even in Narnia, the biblical understanding of magic is underscored. Those who use magic for evil intent (the White Witch in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, and the Magician in The Magician’s Nephew) are the bad guys and looked down on for doing so. Even when the good guys (such as Lucy in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader) who dabble in magic to manipulate for their own gain, they are rebuked by Aslan.

In the opening scene of The Silver Chair, the boy Eustace wants to go back to Narnia where he had previously been. He wonders if they could use magic to get there. Notice the dialogue between him and Jill, who also wants to go there by using magic:

“You mean we might draw a circle on the ground – and write in queer letters in it – and stand inside it – and recite charms and spells?”

“Well,” said Eustace after he had thought hard for a bit. “I believe that was the sort of thing I was thinking of, though I never did it. But now that it comes to the point, I’ve an idea that all those circles and things are rather rot. I don’t think [Aslan] would like them. It would look as if we thought we could make him do things. But really, we can only ask him.”

Magic in Narnia not something to master like at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. Quite the opposite. Magic is something to be feared and learn to make you more obedient to the Divine. Moreover, Lewis goes out of his way in book one of the Narnia series to explain that magical powers of Narnia are not available on earth.

While a committed fundamentalist never will fully embrace the Narnia series, he or she at least owes Lewis fans the dignity of not lumping his works in with secular fantasy literature.

In summary, C.S. Lewis’ Chronicles of Narnia are the best available writings of that genre and have helped millions of Christians (including the writer of this post) to better understand the grace and power and salvation offered only by Christ. May the series continue its popularity for many centuries to come.